[Book Notes] The Outsiders: Eight Unconventional CEOs and Their Radically Rational Blueprint for Success

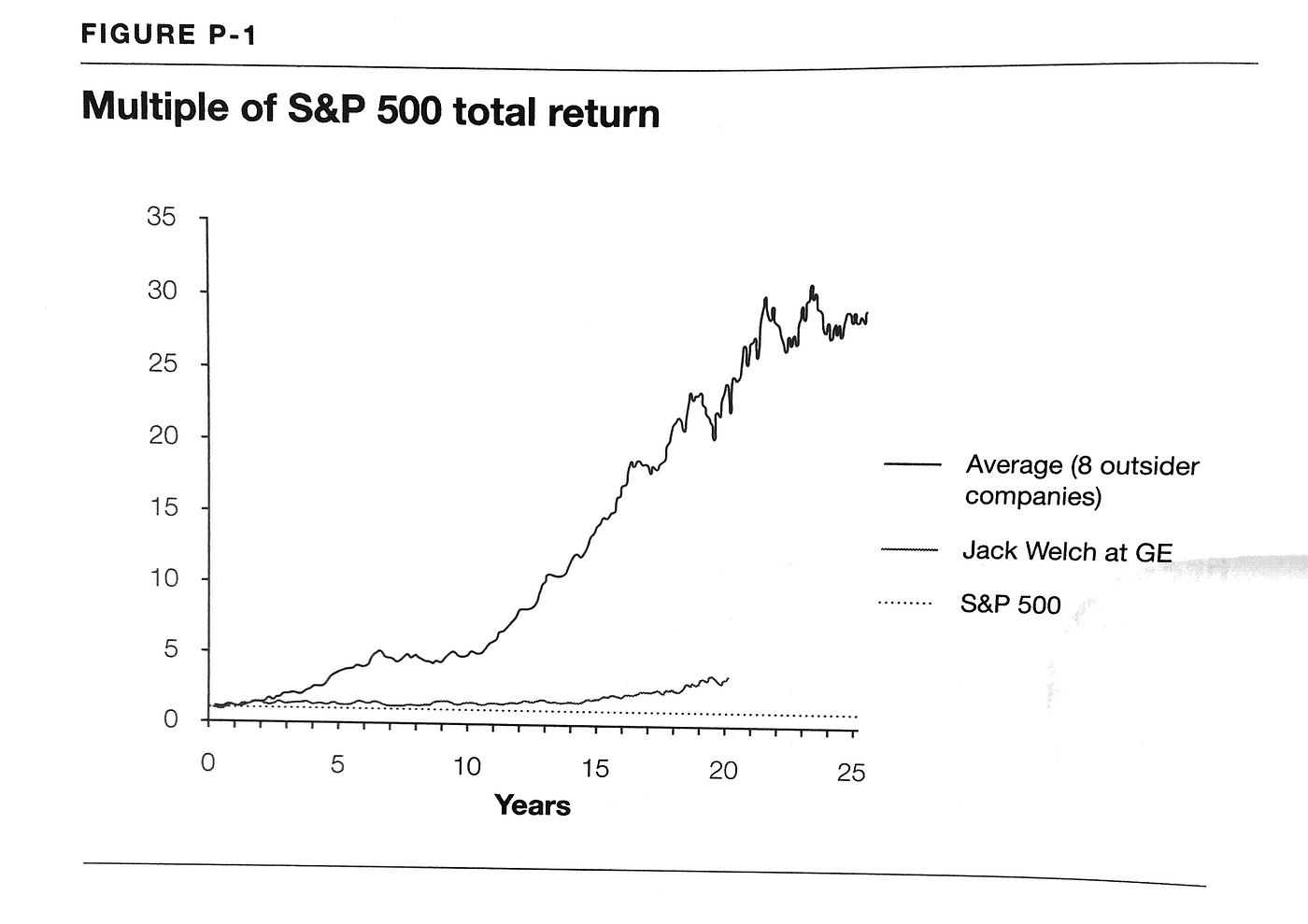

This book looks at a group of CEOs that performed extraordinarily well over long periods of time. The author, William N. Thorndike, Jr. especially likes to compare them against Jack Welch who returned 20% over a period that the S&P averaged 14% annual returns. “The Outsiders” kicked his ass:

How? The extreme tl;dr:

…in their zigging, they followed a virtually identical blueprint: they disdained dividends, made disciplined (occasionally large) acquisitions, used leverage selectively, bought back a lot of stock, minimized taxes, ran decentralized organizations, and focused on cash flow over reported net income.

For a slightly expanded tl;dr scroll to the bottom for a 10-item checklist. (Another is found a few points below, “Overview: Things CEOs should know.)

You’ll see a lot of points repeated in slightly different scenarios. I’ve kept a lot of repetition out here, but it’s instructive to see themes play out in different circumstances.

Everything below is quoted from The Outsiders. Anything in brackets or emboldened is me.

Preface & Introduction

Focusing on Per Share Value

The metric that the press usually focuses on is growth in revenues and profits. It’s the increase in a company’s per share value, however, not growth in sales or earnings or employees, that offers the ultimate barometer of a CEO’s greatness. It’s as if Sports Illustrated put only the tallest pitchers and widest goalies on its cover.

In assessing performance, what matters isn’t the absolute rate of return but the return relative to peers and the market. You really only need to know three things to evaluate a CEO’s greatness: the compound annual return to shareholders during his or her tenure and the return over the same period for peer companies and for the broader market (usually measured by the S&P 500). [pg ix]

Impact of Asset Allocation

Buffett stressed the potential impact of this skill gap [CEOs not being trained in asset allocation], pointing out that “after ten years on the job, a CEO whose company annually retains earning equal to 10 percent of net worth will have been responsible for the deployment of more than 60 percent of all the capital at work in the business.” [pg xiii]

Overview: Things CEOs Should Know

Call it Singletonville, a very select group of men and women who understood, among other things, that:

- Capital allocation is a CEO’s most important job.

- What counts in the long run is the increase in per share value, not overall growth or size.

- Cash flow, not reported earnings, is what determines long-term value.

- Decentralized organizations release entrepreneurial energy and keep both costs and “rancor” down.

- Independent thinking is essential to long-term success, and interactions with outside advisers (Wall Street, the press, etc.) can be distracting and time-consuming.

- Sometimes the best investment opportunity is in your own stock.

- With acquisitions, patience is a virtue…as is occasional boldness.

Interestingly, their iconoclasm was reinforced in many cases by geography. For the most part, their operations were located in cities like Denver, Omaha, Los Angeles, Alexandria, Washington, and St. Louis, removed from the financial epicenter of the Boston/New York corridor.

The residents of Singletonville, our outsider CEOs, also shared an interesting set of personal characteristics: They were generally frugal (often legendarily so) and humbly, analytical, and understated. They were devoted to their families, often leaving the office early to attend school events. They did not typically relish the outward-facing part of the CEO role. They did not give chamber of commerce speeches, and they did not attend Davos. They rarely appeared on the covers of business publications and did not write books of management advice. They were not cheerleaders or marketers or backslappers, and they did not exude charisma.

They were very different from the high-profile CEOs such as Steve Jobs or Sam Walton or Herb Kelleher of Southwest Airlines or Mark Zuckerberg. These geniuses are the Isaac Newtons of business, struck apple-like by enormously powerful ideas that they proceed to execute with maniacal focus and determination. Their situations and circumstances, however, are not remotely similar (nor are the lessons from their careers remotely transferable) to those of the vast majority of business executives.

[pg xvi]

Outsiders are Foxes, not Hedgehogs

Isaiah Berlin, in a famous essay about Leo Tolstoy, introduced the instructive contrast between the “fox,” who knows many things, and the “hedgehog,” who knows one thing but knows it very well. Most CEOs are hedgehogs — they grow up in an industry and by the time they are tapped for the top role, have come to know it thoroughly. There are many positive attributes associated with hedgehogness, including expertise, specialization, and focus.

Foxes, however, also have many attractive qualities, including an ability to make connections across fields and to innovate, and the CEOs in this book were definite foxes. They had familiarity with other companies and industries and disciplines, and this ranginess translated into new perspectives, which in turn helped them to develop new approaches that eventually translated into exceptional results. [pg 5, Introduction]

The best CEOs are the best investors

The business world has traditionally divided itself into two basic camps: those who run companies and those who invest in them. The lessons of these iconoclastic CEOs suggest a new, more nuanced conception of the chief executive’s job, with less emphasis placed on charismatic leadership and more on careful deployment of firm resources.

At bottom, these CEOs thought more like investors than managers. Fundamentally, they had confidence in their own analytical skills, and on the rare occasions when they saw compelling discrepancies between value and price, they were prepared to act boldly. When their stock was cheap, they bought it (often in large quantities), and when it was expensive, they used it to buy other companies or to raise inexpensive capital to fund future growth. If they couldn’t identify compelling projects, they were comfortable waiting, sometimes for very long periods of time (an entire decade in the case of General Cinema’s Dick Smith). Over the long term, this systematic, methodical blend of low buying and high selling produced exceptional returns for shareholders. [pg 6, Introduction]

Greedy when others are fearful

The times [1974–1982, a period that “featured a toxic combination of an external oil shock, disastrous fiscal and monetary policy, and the worst domestic political scandal in the nation’s history”], like now, were so uncertain and scary that most managers sat on their hands, but for all the outsider CEOs it was among the most active periods of their careers — every single one was engaged in either a significant share repurchase program or a series of large acquisitions (or in the case of Tom Murphy, both). As a group, they were, in the words of Warren Buffett, very “greedy” while their peers were deeply fearful. [pg 7, Introduction]

Self-reliance and cash flow

Scientists and mathematicians often speak of the clarity “on the other side” of complexity, and these CEOs — all of whom were quantitatively adept (more had engineering degrees than MBAs) — had a genius for simplicity, for cutting through the clutter of peer and press chatter to zero in on the core economic characteristics of their businesses.

In all cases, this led the outsider CEOs to focus on cash flow and forgo the blind pursuit of the Wall Street holy grail of reported earnings. [pg 9, introduction]

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Chapter 1: Tom Murphy and Capital Cities Broadcasting

A lot of little decisions

As [Tom] Murphy told me, “The business of business is a lot of little decisions every day mixed up with a few big decisions.” [pg 17]

COO CEO partnership

Theirs was an excellent partnership with a very clear division of labor. Burke [COO] was responsible for daily management of operations, and Murphy [CEO] for acquisitions, capital allocation, and occasional interaction with Wall Street. [pg 18]

One reason to acquire

The core economic rationale for the deal was Murphy’s conviction that he could improve the margins for ABC’s TV stations from the low thirties up to Capital Cities’ industry-leading levels (50-plus percent). [pg 19]

Hire the best and leave them alone

In the Capital Cities culture, the publishers and station managers had the power and prestige internally, and they almost never heard from New York if they were hitting their numbers. It was an environment that selected for and promoted independent, entrepreneurial managers. The company’s guiding human resource philosophy, repeated ad infinitum by Murphy, was to “hire the best people you can and leave them alone.” As Burke told me, the company’s extreme decentralized approach “kept both costs and rancor down.” [pg 23]

Investing in the right things in big ways, cut costs everywhere else

As Burke [COO] said in describing his early years in Albany, “Murphy delegates to the point of anarchy.”

They believed that the best defense against the revenue lumpiness inherent in advertising-supported businesses was a constant vigilance on costs, which became deeply embedded in the company’s culture.

Managers were expected to outperform their peers, and great attention was paid to margins, which Burke viewed as “a form of report card.” Outside of these meetings, managers were left alone and sometimes went months without hearing from corporate.

The company [Capital Cities Broadcasting] did not simply cut its way to high margins, however. It also emphasized investing in its businesses for long-term growth. Murphy and Burke realized that the key drivers of profitability in most of their businesses were revenue growth and advertising market share, and they were prepared to invest in their properties to ensure leadership in local markets.

For example, Murphy and Burke realized early on that the TV station that was number one in local news ended up with a disproportionate share of the market’s advertising revenue. As a result, Capital Cities stations always invested heavily in news talent and technology, and remarkably, virtually every one of its stations led in the its local market. In another example, Burke insisted on spending substation ally more money to upgrade the Fort Worth printing plant than Phil Meek had requested, realizing the importance of color printing in maintaining the Telegram’s long-term competitive position. As Phil Beuth, an early employee, told me, “The company was careful, not just cheap.”

The company’s hiring practices were equally unconventional. With no prior broadcasting experience themselves before joining Capital Cities, Murphy and Burke shared a clear preference for intelligence, ability, and drive over direct industry experience. They were looking for talented, younger foxes with fresh perspectives. When the company made an acquisition or entered a new industry, it inevitably designated a top Capital Cities executive, often from an unrelated division, to oversee the new property. In this vein, Bill James, who had been running the flagship radio property, WJR in Detroit, was tapped to run the cable division, and John Sias, previously head of the publishing division, took over the ABC Network. Neither had ay prior industry experience; both produced excellent results. [pg 24]

Increase autonomy to lower turnover

Burke recalls Smith saying, “The system in place corrupts you with so much autonomy and authority that you can’t imagine leaving.” [pg 27]

Funding acquisitions with debt

Murphy also frequently used debt to fund acquisitions, once summarizing his approach as “always, we’ve … taken the assets once we’ve paid them off and leveraged them again to buy other assets.” [pg 27]

Acquisition rules, heuristics, and happy negotiations

Acquisitions were far and away the largest outlets for the company’s capital during Murphy’s tenure.

[Although 2/3 of acquisitions destroy shareholder value, Murphy had a couple key advantages: 1) he never used investment bankers and 2) knew that Burke could fix up the operations to make each company significantly more profitable “lowering the effective price paid.”]

He was known for his sense of humor and for his honesty and integrity.

[Tom] Murphy was a master at prospecting for deals. He was known for his sense of humor and for his honesty and integrity. Unlike other media company CEOs, he stayed out of the public eye (although this became more difficult after the ABC acquisition). These traits helped him as he prospected for potential acquisitions. Murphy knew what he wanted to buy, and he spent years developing relationships with the owners of desirable properties. He never participated in a hostile takeover situation, and every major transaction that the company completed was sourced via direct contact with sellers, such as Walter Annenberg of Triangle and Leonard Goldenson of ABC.

He worked hard to become a preferred buyer by treating employees fairly and running properties that were consistent leaders in their markets.

Murphy knew what he wanted to buy, and he spent years developing relationships with the owners of desirable properties.

Bennett this avuncular, outgoing exterior, however, lurked a razor-sharp business mind. Murphy was a highly disciplined buyer who had strict return requirements and did not stretch for acquisitions — once missing a very large newspaper transaction involved three Texas properties over a $5 million difference in price. Like others in this book, relied on simple but powerful rules in evaluating transactions. For Murphy, that benchmark was a double-digit after-tax return over ten years without leverage. As a result of this pricing discipline, he never prevailed in an auction, although he participated in many. Murphy told me that his auction bids consistently ended up at only 60 to 70 percent of the eventual transaction price.

Murphy had an unusual negotiating style. He believed in “leaving something on the table” for the seller and said that in the best transactions, everyone came away happy.

[pg 29]

Humility in management

Phil meek told me a story about a bartender at one of the management retreats who made a handsome return by buying Capital Cities stock in the early 1970s. When an executive later asked why he had made the investment, the bartender replied, “I’ve worked at a lot of corporate events over the years, but Capital Cities was the only company where you couldn’t tell who the bosses were.” [pg 34]

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Chapter 2: Henry Singleton and Teledyn

When to acquire, when to stop

[Henry Singleton bought 130 companies between 1961 and 1969 almost exclusively with Teledyne’s pricey stock.

[Singleton] did not buy indiscriminately, avoiding turnaround situations, and focusing instead on profitable, growing companies with leading market positions, often in niche markets. [pg 41, Singleton]

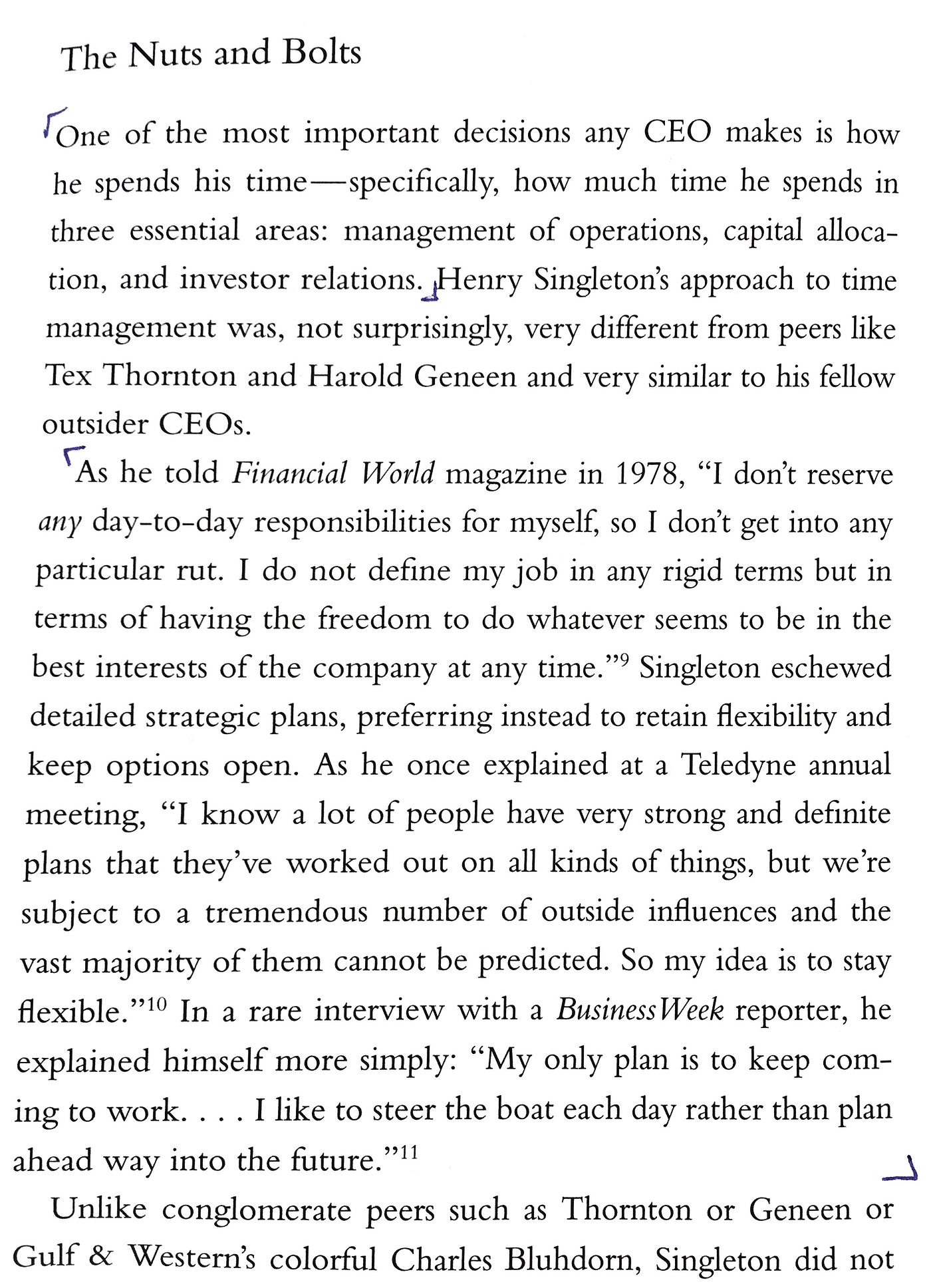

Once Roberts joined the company, Singleton began to remove himself from operations, freeing up the majority of his time to focus on strategic and capital allocation issues.

Shortly thereafter, Singleton became the first of the conglomerators to stop acquiring. In mid-1969, with the multiple on his stock falling and acquisition prices rising, he abruptly dismissed his acquisition team. Singleton, as a disciplined buyer, realized that with a lower P/E ratio, the currency of his stock was no longer attractive enough for acquisitions. From this point on, the company never made another material purchase and never issued another share of stock.

… Over its first ten years as a public company, Teledyne’s earnings per share (EPS) grew an astonishing sixty-four-fold, while shares outstanding grew less than fourteen times, resulting in significant value creation for shareholders. [pg 42 ]

Cash flow focus (again)

In another departure from conventional wisdom, Singleton eschewed reported earnings, the key metric on Wall Street at the time, running his company instead to optimize free cash flow. He and his CFO, Jerry Jerome, devised a unique metric that they termed the Teledyne return, which by averaging cash flow and net income for each business unit, emphasized cash generation and became the basis for bonus compensation for all business unit general managers. [pg 44]

“No one has ever bought in shares as aggressively.”

The conventional wisdom was that repurchases signaled a lack of internal investment opportunity, and they were thus regarded by Wall Street as a sign of weakness. Singleton ignored this orthodoxy, and between 1972 and 1984, in eight separate tender offers, he bought back an astonishing 90 percent of Teledyne’s outstanding shares. As Munger says, “No one has ever bought in shares as aggressively.”

Singleton believed repurchases were a far more tax-efficient method for returning capital to shareholders than dividends, which for most of his tenure were taxed at very high rates. Singleton believed buying stock at attractive prices was self-catalyzing, analogous to coiling a spring that at some future point would surge forward to realize full value, generating exceptional returns in the process.

Not surprisingly, Singleton bought extremely well, generating an incredible 42 percent compound annual return for Teledyne’s shareholders across the tenders.

It’s important, however, to recognize that this obsession with repurchases represented an evolution in thinking for Singleton, who, earlier in his career when he was building Teledyne, had been an active and highly effective issuer of stock.

As Charlie Munger said of Singleton’s investment approach, “ Like Warren and me, he was comfortable with concentration and bought only a few things that he understood well.”

[pg 46]

Not the right thing, but the right thing at the right time

In the words of longtime [Teledyne] board member Faye Sarofim, Singleton believed “there was a time to conglomerate and a time to deconglomerate.” [pg 50]

Optionality & priorities

“If everyone’s doing them…”

When Cooperman asked [Singleton] about them [trendy large share repurchases], Singleton responded presciently, “If everyone’s doing them, there must be something wrong with them.”

“If everyone’s doing them, there must be something wrong with them.”

Warren Buffett & Henry Singleton: Peas in a pod

Many of the distinctive tenets of Warren Buffett’s unique approach to managing Berkshire Hathaway were first employed by Singleton at Teledyne. In fact, Singleton can be seen as a sort of porto-buffett, and there are uncanny similarities between these two virtuoso CEOs, as the following list demonstrates.

--------------------------------------------------------------

Chapter 3: Bill Anders and General Dynamics

Bill Anders’ turnaround plan for General Dynamics

Rationality rules

Anders made the rational business decision [to sell General Dynamic’s F-16 business to Lockheed], the one that was consistent with growing per share value, even though it shrank his company to less than half its former size and robbed him of his favorite perk as CEO: the opportunity to fly the company’s cutting-edge jets. This single decision underscores a key point across the CEOs in this book: as a group, they were, at their core, rational and pragmatic, agnostic and clear-eyes. They did not have ideology. When offered the right price, Anders might not have sold his mother, but he didn’t hesitate to sell his favorite business unit.

This single decision underscores a key point across the CEOs in this book: as a group, they were, at their core, rational and pragmatic, agnostic and clear-eyes.

[pg 68]

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Chapter 4: John Malone and Tele-Communications Inc (TCI)

Accurate, not precise. Settler, not pioneer.

Applying his engineering mind-set [to investment projects], Malone looked for no-brainers, focusing only on projects that had compelling returns. Interestingly, he didn’t use spreadsheets, preferring instead projects where returns could be justified by simple math. As he once said, “Computers require an immense amount of detail… I’m a mathematician, not a programmer. I may be accurate, but I’m not precise.”

Ironically, this most technically savvy of cable CEOs was typically the last to implement new technology, preferring the role of technological “settler” to that of “pioneer.” Malone appreciated how difficult and expensive it was to implement new technologies, and preferred to wait and let his peers prove the economic viability of new services, saying of an early-1980s decision to delay the introduction of a new setup box, “We lost no major ground by waiting to invest. Unfortunately, pioneers in cable technology often have arrows in their backs.”

[pg 102]

Heuristics for quick, reliable decisions

He was also, however, a value buyer, and he quickly developed a simple rule that became the cornerstone of the company’s acquisition program: only purchase companies if the price translated into a maximum multiple of five times cash flow after the easily quantifiable benefits from programming discounts and overhead elimination had been realized. This analysis could be done on a single sheet of paper (or if necessary, the back of a napkin). It did not require extensive modeling or projections.

Malone’s simple rule allowed him to act quickly when opportunity presented itself. When the Hoak family, owners of a million-subscriber cable business, decided to sell in 1987, Malone was able to strike a deal with them in an hour. He was also comfortable walking away from transactions that did not meet the rule. Paul Kagan, a longtime industry analyst, remembered Malone walking away from a sizable Hawaiian transaction that was only $1 million over his target price.

[pg 105]

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Chapter 5: The Widow Takes the Helm

Save, then buybuybuy

With her board, she subjected all potential transactions to a rigorous, analytical test. As Tom Might summarized it, “Acquisitions needed to earn a minimum 11 percent cash return without leverage over a ten-year holding period.” Again, this seemingly simple test proved a very effective filter, and as Might says, “Very few deals passed through this screen. The company’s whole acquisition ethos was to wait for just the right deal.”

As her son Donald says Today, “The deals not done were very important.” Another large newspaper would have been a boat anchor around our necks today.”

Graham’s uncharacteristic buying spree during the recession of the early 1990s was also telling. With an exceptionally strong balance sheet, she became an active buyer at a time when her over leveraged peers were forced to the sidelines. Taking advantage of dramatically reduced prices, the Post opportunistically purchased a series of rural cable systems, several underperforming television stations in Texas, and a number of education businesses all of which proved to be extremely accretive to shareholders.

[pg 119]

Connecting with Buffett

The decision to welcome Buffett into the fold [on the board of Washington Post] was highly independent and unusual one at the time. In the mid-1970s, Buffett was virtually unknown. Again, the choice of a mentor is a critically important decision for any executive and Graham chose unconventionally and extraordinarily well. As her son Donald has said, “Figuring out this relatively unknown guy was a genius was one of the less celebrated, best moves she ever made.”

[pg 124]

“Should you find yourself in a chronically leaking boat, energy devoted to changing vessels is likely to be more productive than energy devoted to patching leaks.” — Warren Buffett

------------------------------------

Chapter 6: Bill Stiritz and Ralson Purina

Simple buying

[Bill Stiritz’s] protege, Pat Mulcahy, who would later run the business [Ralston Purina], described Stiritz’s approach to the seminal Energizer acquisition: “When the opportunity to buy Energizer came up, a small group of us met at 1:00 PM and got the seller’s books. We performed a back of the envelope LBO model, met again at 4:00 PM and decided to bid $1.4 billion. Simple as that. We knew what we needed to focus on. No massive studies and no bankers.” Again, Stiritz’s approach (similar to those of Tom Murphy, John Malone, Katherine Graham, and others) featured a single sheet of paper and an intense focus on key assumptions, not a forty-page set of projections.

[pg 143]

“Leadership is analysis.”

Stiritz was fiercely independent, and actively disdained the advice of outside advisers. He believed that charisma was overrated as a managerial attribute and that analytical skill was a critical prerequisite for a CEO and the key to independent thinking: “Without it, chief executives are at the mercy of their bankers and CFOs.” Stiritz observed that many CEOs came from functional areas (legal, marketing, manufacturing, sales) where this sort of analytical ability was not required Without it, he believed they were severely handicapped. His counsel was simple: “Leadership is analysis.”

[pg 144]

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Chapter 8: Warrenn Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway

You shape your houses and then your houses shape you. — Winston Churchill

When Buffett became Buffett

Fear of inflation was a constant theme in Berkshire’s annual reports throughout the 1970s and into the early 1980s. The conventional wisdom at the time was that hard assets (gold, timber, and the like) were the most effective inflation hedges. Buffett, however, under Munger’s influence and in a shift from [Benjamin] Graham’s traditional approach, had come to a different conclusion. His contrarian insight was that companies with low capital needs and the ability to raise prices were actually best positioned to resist inflation’s corrosive effects.

This led him to invest in consumer brands and media properties — businesses with “franchises,” dominant market positions, or brand names. Along with this shift in investment criteria came an important shift to longer holding periods, which allowed for long-term pretax compounding of investment values.

It is hard to overstate the significance of this change. Buffett was switching at mid career from a proven, lucrative investment approach that focused on the balance sheet and tangible assets, to an entirely different one that looked to the future and emphasized the income statement and hard-to-quantify assets like brand names and market share. To determined margin of safety, Buffett relied now on discounted cash flows and private market values instead of Graham’s beloved net working capital calculation. It was not unlike Bob Dylan’s controversial and roughly contemporaneous switch from acoustic to electric guitar.

[pg 173]

Patience…(2 years)…pounce!

After the Capital Cities transaction [1986], he [Buffett] did not make another public market investment until 1989, when he announced that he had made the largest investment in Berkshire’s history: investing an amount equal to one-quarter of Berkshire’s book value in the Coca-Cola Company, purchasing 7 percent of its shares.

[pg 175]

Big & lumpy over smaller & smooth

Over time, Buffett evolved an idiosyncratic strategy for his insurance operations that emphasized profitable underwriting and float generation over growth in premium revenue. This approach, wildly different from most other insurance companies, relied on a willingness to avoid underwriting insurance when pricing was low, even if short-term profitability might suffer, and, conversely, a propensity to write extraordinarily large amounts of business when prices were attractive.

As Buffett has said, “Charlie and I have always preferred a lumpy 15 percent return to a smooth 12 percent return.”

[pg 179]

Being a CEO has made me a better investor, and vice versa. — Warren Buffett

Concentration can decrease risk

“We believe that a policy of portfolio concentration may well decrease risk if it raises, as it should, both the intensity with which an investor thinks about a business and the comfort level he must feel with its economic characteristics before buying into it.” [Warren Buffett]

[pg 184]

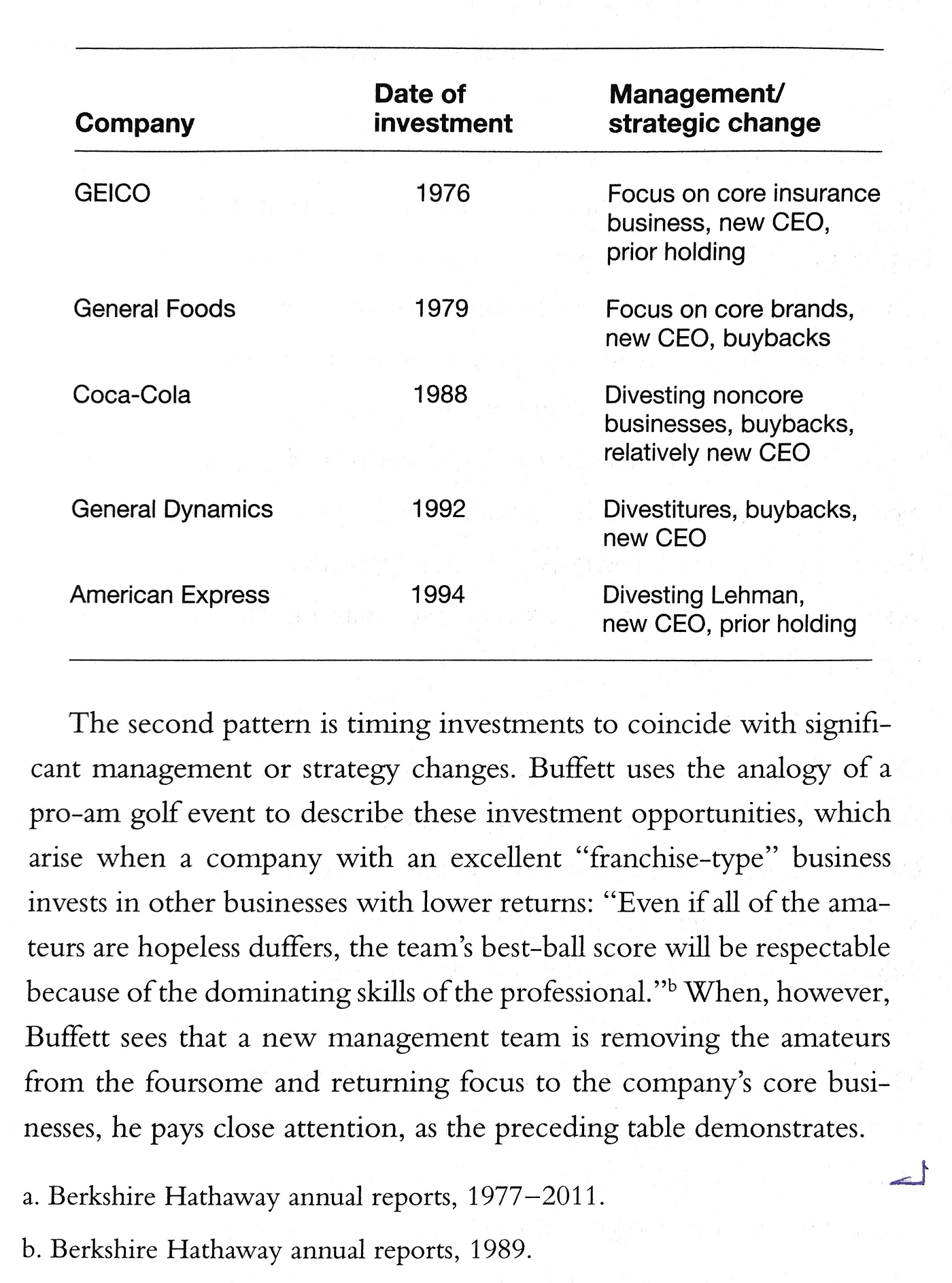

Two interesting Buffett trading trends

“Hire well, manage little”

He [Buffett] summarizes this approach to management as “hire well, manage little” and believes this extreme form of decentralization increases the overall efficiency of the organization by reducing overhead and releasing entrepreneurial energy.

Warren is mad chill

Warren wrap-up: quality matters

All of this adds up to something much more powerful than a business or investment strategy. Buffett has developed a worldview that at its core emphasizes the development of long-term relationships with excellent people and businesses and the avoidance of unnecessary turnover, which can interrupt the powerful chain of economic compounding that is the essence of long-term value creation.

In fact, Buffett can perhaps best be understood as a manager/investor/philosopher whose primary objective is turnover reduction. Berkshires many iconoclastic policies all share the objective of selecting for the best people and businesses and reducing the significant financial and human costs of churn, whether of managers, investors, or shareholders. To Buffett and Munger, there is a compelling, Zen-like logic in choosing to associate with the best and in avoiding unnecessary change. Not only is it a path to exceptional economic returns, it is a more balanced way to lead a life; and among the many lessons they have to teach, the power of these long-term relationships may be the most important.

What makes him a leader is precisely that he is able to think through things himself. — William Deresiewicz

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

Chapter 9: Radical Rationality

How to be an Outsider

Always Do the Math

[Make sure to engage rationality in decisions. Outsider CEOs often use “one-pager” analyses to do this.]

The Denominator Matters

These CEOs shared an intense focus on maximizing value per share. To do this, they didn’t simply focus on the numerator, total company value, which can be grown by any number of means, including overpaying for acquisitions or funding internal capital projects that don’t make economic sense. They also focused intently on manning the denominator through the careful financing of investment projects and opportunistic share repurchases. These repurchases were not made to prop up stock prices or to offset option grants (two popular rationales for buybacks today) but rather because they offered attractive returns as investments in their own right.

A Feisty Independence

The outsider CEOs were master delegators, running highly decentralized organizations and pushing operating decisions down to the lowest, most local levels in their organizations. They did not, however, delegate capital allocation decisions. As Charlie Munger described it to me, their companies were “an odd blend of decentralized operations and highly centralized capital allocation,” and this mix of loose and tight, of delegation and hierarchy, proved to be a very powerful counter to the institutional imperative.

Charisma is Overrated

… As a group, they were not extroverted or overly charismatic. In this regard, they had the quality of humility that Jim Collins emphasized in his excellent Good to Great. They did not seek (or usually attract) the spotlight.

The outsider CEOs, like Stonecipher and Tillerson, tended to dance when everyone else was on the sidelines and to cling shyly to the periphery when the music was loudest. They were intelligent contrarians willing to lean against the wall indefinitely when returns were uninteresting.

…in their zigging, they followed a virtually identical blueprint: they disdained dividends, made disciplined (occasionally large) acquisitions, used leverage selectively, bought back a lot of stock, minimized taxes, ran decentralized organizations, and focused on cash flow over reported net income.

Although the outsider CEOs were an extraordinarily talented group, their advantage relative to their peers was on of temperament, not intellect. Fundamentally, they believed that what mattered was clear-eyed decision making, and in their cultures they emphasized the seemingly old-fashioned virtues of frugality and patience, independence and (occasional) boldness, rationality and logic.

The Outsiders Compared

The Outsiders Checklist

No comments:

Post a Comment